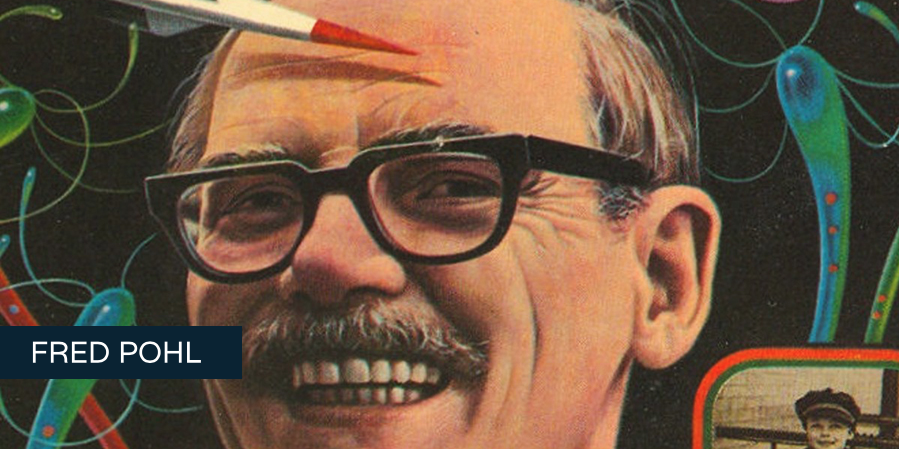

My introduction to the one-volume German edition of his HEECHEE SAGA (Gateway novels).

Fred Pohl was there at the beginning, the Big Bang as it were, when what is today a vast commercial and cultural universe (some would say, wasteland) that includes film and TV as well as books and magazines, started as an improbable singularity known only to precocious, oddball teenagers (mostly boys) obsessed with a new “literature” that was just appearing in the pulp magazines that they could buy for a dime or a nickel.

They first called it scientifiction, but the name didn’t stick.

Science Fiction did.

It was 1935 in Brooklyn. The USA was in the throes of what we still call the “Great Depression,” perhaps because we miss it so keenly. Today we are lonely for the past but back then we hungered for the future, we lusted for it, and SF delivered it to the eager and the willing.

As a literary form, Science Fiction had been around since Verne and Wells, and perhaps even Mary Shelley with her mournful electrically-animated monster. Some would claim that it began earlier, with Gulliver’s Travels or even Aristophanes’ “The Birds.” But surely we can all agree that as a modern phenomenon, a cultural and commercial commodity as well as a literary curiosity, it began in the 1920s and ‘30s when the “pulps” appeared on American newsstands with garish covers depicting rocket ships, ray guns, robots and buxom women threatened by bug-eyed monsters (‘bems’). It was, as the magazine titles promised, Amazing; it was Astounding, it was Thrilling.

Pohl describes those heady days in his brilliant memoir, The Way the Future Was: “My head was popping with space ships and winged girls and cloaks of invisibility, and I had no one to share it with.”

Pohl describes those heady days in his brilliant memoir, The Way the Future Was: “My head was popping with space ships and winged girls and cloaks of invisibility, and I had no one to share it with.”

He was not to be lonely long.

Science Fiction was fishing for souls. If the lurid covers were the bait, and the stories the hooks, the net was the clubs that the magazines created to haul in new readers: the Science Fiction League and its many descendants.

The catch was extraordinary: Pohl, along with his friend and collaborator Cyril Kornbluth, Isaac Asimov (another Brooklyn kid), James Blish, Judith Merril, Donald Wollheim and a vast school of others, including Ray Bradbury and Jack Williamson, who showed up at the first SF conventions.

“Most people wanted to talk about what they had eaten or bought or done,” Pohl remembers today. “We wanted to talk about what we had read.” And these early devotees did more then talk. They set to work creating what we know as SF today.

Fred Pohl was a wunderkind. As a pimply teenager he was editing the fanzine for the International Scientific Society (which was, he points out, neither international nor scientific). He slept every other day and wrote the rest of the time, or hung out talking space ships and winged girls with his colleagues in the Futurians, the first split off the extremely fissionable SF world.

Pohl didn’t bother finishing high school. He was far too busy. By age nineteen, in the late 1930s, he was editing two magazines on Forty Second Street: Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories. He was also writing his own stories under an incredible panoply of pen names, representing his friends (and his pseudonyms) as an agent, and of course attending and organizing (and occasionally boycotting) SF conventions as one of the original fans.

Then there came a war. After serving in both Italy and France, Pohl returned to New York make a living in the field he had done so much to help create. The Great Depression was over. America (and SF with it) was booming; the boy readers had grown up and even brought a few girls along with them. No longer satisfied with the pulps, they wanted novels. Pohl wrote his own and collaborated with Kornbluth and Williamson, developing his famous Trollope-like regimen that resulted in four pages a day, like clockwork; meanwhile bringing the magazines he edited (including Galaxy and If) to new levels that accounted for most of the major SF awards.

It was a career that would stagger many, and satisfy most. But not Fred Pohl.

Cut to the 1970s, when Pohl discovered he was tired of editing, tired of agenting. He began writing more seriously. In the meantime, SF itself had turned a corner with the New Wave. The two events together produced that rarest of all things in American literature, a second act, and a brilliant one at that.

Fred Pohl, who had always been a star, went nova.

Enter the Heechee.

`It is a mark of Pohl’s satiric genius that in GATEWAY, humankind’s first voyages into the depths of interstellar space are made not for science, or even glory, but for money.

Loot.

Gateway (later called “wrinkle rock”) is an asteroid discovered in an eccentric orbit around the sun. It is criss-crossed with tunnels and clustered with spaceships, all of which are preprogrammed for a round trip to a different, an undisclosed, and often disastrous destination.

All humans have to do is climb aboard and ride.

The ships and the honeycombed asteroid itself are all artifacts of the Heechee, a mysterious and long-departed (or so it seems) race that once colonized vast sectors of the universe.

Some “Gateway prospectors” return as millionaires, loaded with valuable Heechee artifacts and gadgets, while others return tangled in their own entrails, or mad as hatters; or not at all.

The one thing they never (or almost never) encounter is the Heechee themselves. Pohl, who had always grounded his work in the actual mysteries of science, speculated that even if there were other civilizations in a Universe so vast in both Space and Time, it was unlikely that they their timelines would intersect with ours.

Thus humankind‘s story begins when the Heechee’s is running out. Or almost.

Thus humankind‘s story begins when the Heechee’s is running out. Or almost.

GATEWAY burst upon the SF world like a new star. It was hard for many to believe that it was written by one of the most familiar names in the field. The writing is difficult at times, brilliant always: allusive, tender, erotic, and often wry and humorous.

The novel exhibits Pohl’s characteristic distrust of authority, his scorn for capitalism’s excesses, and his materialist (ie, Marxist) view of how history is made, and how it in turn makes mankind. All these concerns carried over from SF’s depression-era origins. But GATEWAY is also a departure, reflecting the psychological preoccupations and literary predilections of the New Wave that had so recently opened up new territory in SF.

The journey of prospector Robinette Broadhead is as much inward as outward. His story is told elliptically, much of it in the form of a dialogue with his artificial psychotherapist, as Broadhead tries to come to terms with the fact that his spectacular success as a prospector has come with a disastrous personal cost-—the loss of the woman he loves.

In Pohl’s Universe, as in Einstein’s, there is no free lunch.

GATEWAY swept every award in the field: the Hugo (not Pohl’s first, but his first for a novel), the Nebula and the Locus awards. And there was more to come.

BEYOND THE BLUE EVENT HORIZON is, as its title might suggest, even more daring, and more difficult. Broadhead is now a background character, and those in the foreground (Gateway prospectors, all) include a horny teen, a grumpy old man, and a not-so-innocent orphan. The mysterious “gifts” bestowed on humanity by the Heechee now include a periodic psychic plague that strikes the Earth at regular intervals, causing death and destruction.

In HEECHEE RENDEZVOUS, the Heechee themselves finally emerge in all their wizened glory—smelling faintly of ammonia, weary with wisdom, and as bemused by us (whom they have known from our earliest hominid days) as we are by them. They are especially puzzled by money, which they regard as a “rough servo-mechanism for social priority setting.”

Pure Pohl.

The novels have proven immensely popular and have spurred countless imitators. GATEWAY was even made into a popular game, which is fitting, since the voyages them selves were a kind of game, a sort of Russian roulette one played for fortune or death.

As an author, editor, agent and anthologist, Fred Pohl helped create the SF we know, celebrate and love today. He nurtured (and coddled, and berated) the greatest talents in the field, even while creating such classics as MAN PLUS and THE SPACE MERCHANTS.

But his most amazing accomplishment was perhaps the re-creation of himself, as an author, with the Heechee Saga, which functions as our “gateway” into a fully realized, intricate and inexhaustible fictional world of “wrinkle rocks,” Kugelblitz, Assassins who make war on matter itself, Dream Seats, Albert Einstein simaculara, Voodoo Pigs, and CHON food.

A universe that is still as fresh, as surprising and as thought-provoking today as when it was penned, some thirty years ago.

(Thanks for your interest in my work. If you enjoyed this little piece, please give a dollar to a homeless person.)