On a cold December night in 1907, some 300 to 500 men, armed and mounted in columns of twos, all wearing masks and white sashes, rode into the small Kentucky city of Hopkinsville. They disarmed the local police, occupied the telegraph and telephone offices, and dynamited two warehouses filled with tobacco belonging to James Duke’s American Tobacco Company.

Then while the flames roared, they destroyed the local newspaper, and at the mournful sound of a hunter’s horn, they formed up in the center of town, holstered their weapons, and rode off into the night.

Then while the flames roared, they destroyed the local newspaper, and at the mournful sound of a hunter’s horn, they formed up in the center of town, holstered their weapons, and rode off into the night.

It was, The New York Times reported with alarm, the first military occupation of an American city since the end of the Civil War, some forty years before. It brought to national attention what was to become known as the Black Patch War.

Tobacco is a versatile plant with many varieties that can grow even in northern and tropical climes. But it is especially adapted to the humid subtropical American South. Shipped in hogsheads from Virginia to England, it was the primary source of wealth for the Southern colonies. Both Washington and Jefferson were tobacco planters. After independence climate and tradition established it as the main cash crop in the Upper South—Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, and later, west of the Blue Ridge, in Kentucky and Tennessee.

A particularly valuable strain of fire-cured leaf, mainly used for “plug” or chewing tobacco, was established in a broad area of western Kentucky and north-central Tennessee, about the size of Massachusetts.

This area, called the Black Patch, centered around Hopkinsville and Clarksville, Tennessee, was plantation country. Tobacco requires little land but much labor, and slave labor made the Black Patch almost as rich as the cotton country to the south. During the Civil War, the area was heavily pro-Confederate, though Kentucky never successfully seceded.

This area, called the Black Patch, centered around Hopkinsville and Clarksville, Tennessee, was plantation country. Tobacco requires little land but much labor, and slave labor made the Black Patch almost as rich as the cotton country to the south. During the Civil War, the area was heavily pro-Confederate, though Kentucky never successfully seceded.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis was from the Black Patch.

During the Civil War, western Kentucky was under Union occupation, but its sympathies never altered. After the war, little changed, as the planters retained their land and wealth, and many of the freed slaves remained as sharecroppers and tenant farmers.

The prosperity after the Civil War made the dark fire-cured leaf of the Black Patch even more valuable. The growers settled back into their traditional Southern way of life. Tobacco processing and manufacturing was centered in North Carolina, where James Buchanan Duke made a fortune selling “Duke’s Mixture,” then leveraged that capital into one of the great Robber Baron “trusts,” the American Tobacco Company.

It was Duke who changed the game. By the early twentieth century all the Black Patch tobacco buyers, formerly independent speculators, were under Duke’s control, and the prices dropped from eight and ten cents to four, three and even two cents a pound.

The wealth and power of the planters was threatened. They were even in danger of losing their laborers. The Nashville Banner warned of a “black exodus” as tenants and sharecroppers were lured away to the more profitable cotton country to the south, or the relative freedom of the northern cities.

It was time to strike back.

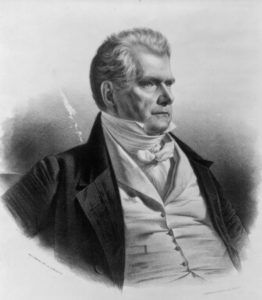

It was a Tennessee planter, Felix Grundy Ewing, “The Moses of the Black Patch,” who saw the need for organization. In the Fall of 1904 (when the tobacco crop was in the barn) Ewing and a few other big planters put out the call for a gathering in Guthrie, Kentucky, right on the Kentucky-Tennessee line.

It was a Tennessee planter, Felix Grundy Ewing, “The Moses of the Black Patch,” who saw the need for organization. In the Fall of 1904 (when the tobacco crop was in the barn) Ewing and a few other big planters put out the call for a gathering in Guthrie, Kentucky, right on the Kentucky-Tennessee line.

Ten thousand showed up in the tiny town of less than a thousand. Not just the planters, but their tenants and ‘croppers whose tobacco “on shares” was their only source of cash. Many of the smaller hill country farmers showed up as well. Merchants, doctors, lawyers, and craftsmen also rallied, since the prosperity of the entire region rested on tobacco prices.

Buggies, mules and horses filled the Guthrie fairgrounds. Barbecue and burgoo, moonshine and fiery speeches were eagerly consumed as thousands lined up to join the new Planters Protective Association (PPA). Growers agreed to deliver their dark-fire only to the PPA, which would hold it off the market until they got a fair price—which they defined at the time as eight cents a pound.

In the months following Guthrie, PPA organizers were dispatched throughout the Black Patch. Meetings were held in churches, stores and school houses in every county, denouncing the crimes of Duke’s trust, until even many of the fiercely independent small farmers came on board.

Rich and poor alike rallied. The PPA spoke for the Black Patch. It was a regional struggle to preserve a traditional way of life that many loved and most at least tolerated. But Duke still held a trump card. Small farmers relying on tobacco for cash couldn’t afford to stash their crop in PPA warehouses when Duke’s ATC buyers would buy it “in the barn” before it went to market. Duke was delighted to pay eight cents a pound to growers willing to sidestep the PPA.

Ewing and the PPA leadership intensified their social pressure. A merchant who spoke against the PPA or tolerated the “hillbillies” (as the independents came to be called) found his customers dropping away. Dissenting preachers watched their pews empty out. Families were torn asunder, brother against brother, just as during the hated war.

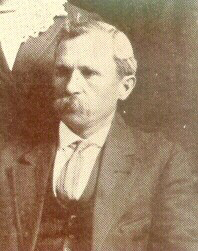

James Amoss, MD, of tiny Cobb, Kentucky, was the very template of the Southern gentleman. The son of a Confederate officer, he was not a planter but he knew tobacco and its importance to the area; he knew the planters and he saw their problems as his own.

James Amoss, MD, of tiny Cobb, Kentucky, was the very template of the Southern gentleman. The son of a Confederate officer, he was not a planter but he knew tobacco and its importance to the area; he knew the planters and he saw their problems as his own.

As a youth, Amoss had attended The Ferrell Military Institute in Hopkinsville, where he had thrilled to the exploits of Stonewall Jackson and Nathan Bedford Forrest. He learned Southern history, military tactics—and a schoolboy’s trick of blowing across the muzzle of a pistol to make a sound like a hunter’s horn that could be heard a quarter mile away.

Amoss loved military lore, but he was destined to be a doctor like his father. After medical school in Ohio, Amoss returned to the Black Patch to serve his local community. Respected by both black and white, he settled into a peaceful and prosperous middle age.

His prized possession was the Army Colt revolver his father had been allowed to keep after Appomattox.

His closest friend was Guy Dunning, fifteen years younger, but also an educated man who had attended Centre College in the Bluegrass. Dunning was a planter whose dozen tenants worked 2500 acres of wheat, corn and dark-fire tobacco.

Amoss, a fatherly mentor at fifty, loved Dunning; Dunning worshipped Amoss. They were to become close allies in a unique and secret enterprise.

It is not known if Amoss was at the first Guthrie gathering, but he was eager to join the PPA, and was soon in the leadership, close to Ewing himself. The second or “anniversary” Guthrie gathering in 1905 was an even greater success than the first, with an estimated 20,000 attending. The PPA now controlled some seventy percent of the tobacco in the Black Patch, and the mood was celebratory. It climaxed in a parade several miles long, with planters, their supporters, Southern Belles bearing bouquets of dark leaf instead of flowers, grizzled Confederate vets, and the rear brought up by a thousand black sharecroppers, who saw their interests, at least temporarily, aligned with those of the planters. Black farmers were welcomed into the PPA, unusual for those apartheid times, and indeed a higher percentage of blacks than whites were members.

The PPA’s first year had exceeded expectations, but the leadership was worried. Recalcitrant growers, some even PPA members, were selling tobacco “in the barn” for Duke’s temporarily inflated prices. And Duke’s resources were apparently limitless. The PPA was facing the same problem unions faced against giant corporations. How to deal with opportunists and scabs?

Persuasion first, then shaming … then force.

Some three weeks after the 1905 Guthrie tobacco jubilee, another PPA meeting was held, this one by invitation only. Fewer than a hundred gathered in the tiny Stainhouse School which was also, symbolically, right on the Kentucky-Tennessee line.

Ewing himself, and the PPA’s public leadership, carefully stayed away. Dr. Amoss, in legend and in rumor, opened the meeting by asking all the members who were willing to fight and die for the cause to stand. Most did. Those who didn’t were asked to leave.

Dr. Amoss then proceeded to build his clandestine military organization. They called themselves the Silent Brigade, or more informally the “possum hunters,” since their activities were to be mostly nocturnal.

Oaths were taken and secret handshakes and passwords memorized. The “Stainhouse Resolutions” were adopted, vowing loyalty to the PPA and severe penalties to those who cooperated with Duke’s hated ATC trust.

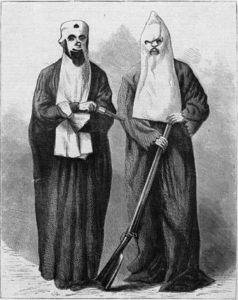

Silent Brigade lodges were formed in every Black Patch county, each lodge with a captain, all answerable to Amoss. Military discipline was established, and in many counties the lodges drilled openly with arms. The uniform was a white sash-and a mask.

Soon after the formation of the Silent Brigade, “hillbilly” farmers found their plant beds scraped or sown with salt. Those who resisted were pulled from their houses and horsewhipped by masked men wearing white sashes.

Most of these raids were never reported, the victims being warned to silence as well as obedience. But they were well known, and discussed in whispers throughout the Black Patch.

It was Kentucky Congressman Augustus Owsley Stanley who gave the Silent Brigade its enduring name. Though a supporter of the PPA, Stanley feared vigilantism and denounced what he called the “Night Riders,” and the name stuck.

Though the PPA was open to black farmers and sharecroppers, the Night Riders were almost entirely white. Under Amoss’s command, strict secrecy was maintained. Raids were planned and new members sworn in, “on bended knee,” under cover of night in remote swamps and woods protected by armed sentries.

The early raids were relatively bloodless if often brutal. Buyers for Duke were first warned, then threatened, then dragged from their hotels and whipped or beaten. Non-compliant farmers found their plant beds scraped, their barns and sometimes even their homes torched.

The “possum hunters” were getting their message across, and it was for the most part, a message supported by the community. A word of warning often sufficed. If not, a letter signed “The Night Riders” might be found, wrapped around rifle cartridges or a bundle of matches, and nailed to a barn door.

The PPA of course claimed no connection with the Night Riders but expressed sympathy with their goals. “We fear no judge nor jury,” was Amoss’s boast, and it proved true. Some Night Riders were identified but never convicted, as it was impossible to assemble an all-male, all-white jury in the Black Patch that didn’t contain at least a few Night Riders.

As volunteers flocked to join his secret army, Amoss pondered a change in tactics. The attacks on individual farmers were growing counterproductive. Even “hillbillies” had families and friends.

Amoss summoned lodges from several counties for a dramatic escalation—a raid on an ATC warehouse in Princeton, a small town south of Hopkinsville.

Late one fall night in 1907, the town awoke to a strange sound: two hundred horses muffled with burlap bags on their hoofs. A worried call to the local telephone switchboard was answered by a gruff male voice: “The Night Riders are here.” Minutes later, a blast rocked the town and a tobacco warehouse went up in flames.

The Princeton raid was not national news but it gave the Night Riders a new image in the Black Patch as a disciplined and powerful force.

Hopkinsville was fully intended to be national news.

The mayor, Charles Meacham, was also the editor of the Hopkinsville Kentuckian, which had editorialized against the Night Riders. After Princeton, Meacham feared an attack on Hopkinsville, the most important city in the Black Patch: a huge tobacco market, and a transportation hub served by two railroads. The local militia, was placed on alert, fearing an attack was imminent.

Amoss responded by planting false rumors, which had the militia mobilized, then looking foolish when nothing happened. Meanwhile Amoss gathered his troops in silence. He also infiltrated squads into the town.

On the night of December 6, hundreds of horsemen gathered at a country church near Hopkinsville. They watered their horses and donned masks and white sashes, waiting for a sign from a modest-looking man in a brown cloth coat and a slouch hat who was consulting a pocket watch.

At 1:00 am Dr. Amoss gave the sign and the Night Riders mounted up, in columns of twos. Amoss took the lead with Dunning at his side.

Military order, perfect silence.

As the Night Riders closed on the town, the implanted Hopkinsville squads went into action. The police and the militia were swiftly disarmed. The ladies in the telephone switchboard were politely taken into custody. The telegraph lines were cut and the railroad depots occupied.

The town was quiet. The few people found on the streets were gently, and some not so gently, taken into custody. Then the silence was shattered as two huge tobacco warehouses were dynamited with a blast heard for miles. Flames lighted the skies, and a flying squad made quick work of the Kentuckian office, smashing the presses, scattering type, and chasing the mayor/editor into hiding in the coal bin of a Baptist church.

By now a few lights had come on, but they were quickly extinguished with warning shots.

The eerie sound of a hunter’s horn called the troops to reassemble; it was Amoss blowing across the muzzle of his Army Colt. Hostages were warned and released, and the Night Riders formed up for withdrawal.

Then Amoss himself appeared, riding into the ranks.

A few cheers. Then confusion and horror …

The “general’s” face was streaked with blood, streaming down from his hat. In an exchange of shots with a sniper, Dr. Amoss himself had been hit, perhaps by friendly fire.

Raising a blood-stained hand, he called for calm, and passed off command to his trusted lieutenant, Dunning, who ordered the withdrawal.

The town was left silent except for the roar of the flames and the thunder of hooves as the Night Riders departed.

Though bloody, Amoss’s wound was only skin deep. He hid the bandages under his hat as he tended to his patients over the next few weeks. There were few Night Rider raids during the Christmas holidays, and the Black Patch was silent, waiting with bated breath.

The wait wasn’t long. In January, the Kentucky town of Russelville, home to two ATC warehouses, heard the muffled tramp, the creaking of harness, the “hunters horn” and the dynamite blasts. No one was injured, and Duke’s ATC lost another $200,000 worth of “hillbilly” tobacco.

The wait wasn’t long. In January, the Kentucky town of Russelville, home to two ATC warehouses, heard the muffled tramp, the creaking of harness, the “hunters horn” and the dynamite blasts. No one was injured, and Duke’s ATC lost another $200,000 worth of “hillbilly” tobacco.

As spring of 1908 approached, the larger military maneuvers ceased. Amoss had made his point: the Night Riders ruled the Black Patch. Riders in small groups struck nightly, burning barns, scraping plant beds, horsewhipping “hillbillies”—then melted back into the population, guerrilla style.

These were local operations, and the masks served not so much to hide the identities of the Night Riders as to enable potential witnesses to “recognize nobody.”

As if anyone would dare. Flushed with the arrogance and prestige of success, the Night Riders’ numbers had grown to an estimated ten thousand across the Black Patch. They had proven themselves immune to local law enforcement.

As the raids became more local, and often more brutal, the opposition grew bolder. Armed “hillbillies” began guarding their fields by night, and attempted an ambush or two on Night Rider bands. There were even assassination attempts against “General” Amoss, who disappeared entirely for months in 1908, but continued to direct his forces from underground, protected by his many friends and neighbors.

A local tobacco buyer and businessman took to openly taunting the PPA. In response, Night Riders destroyed his distillery and lashed him to within an inch of his life. Then a small black community of his workers was terrorized KKK style and ordered to leave the state. Things were getting meaner. Informers and suspected traitors were “disappeared,” their bodies found in remote swamps or abandoned wells–or not at all.

The Night Riders still ruled the Black Patch, but outside forces began to speak out against them. The Louisville Courier Journal called for Law and Order, denouncing the Night Riders as the “shame” of Kentucky.

The new Kentucky governor, Augustus Willson, a lawyer who had once worked for the Duke trust, ordered several companies of Kentucky militia into the Black Patch. Their roadblocks and patrols restricted the activities of the Night Riders somewhat, but also increased their popularity, as the militia, mostly “rude mountain boys” from eastern Kentucky, were seen as occupiers.

Some arrests were made but the only people who went to jail were those who fought back against the Night Riders.

“Shirt-sleeve” night riders, who no longer answered to Amoss, began to punish personal grudges and terrorize black communities. Unlike the planters, inclined to protect their tenants, the small farmers and “hillbillies” resented blacks as competition, and unleashed the racial violence that had always underlain the Southern way of life.

Growers, some even in the PPA, were ordered to replace their black tenants with whites … or suffer the consequences.

The small town of Birmingham, formed by freed slaves after the war, was torched and those who refused to flee were murdered in cold blood.

White farmers fled also. Ohio River towns in Indiana and Illinois became home to displaced Kentuckians. This led to an effective new strategy, as civil suits were filed against Amoss and the Night Riders from Illinois and Indiana. These interstate suits fell under federal jurisdiction, and acquitals were no longer assured. Night Rider lodges often found themselves raising funds to pay off the judgments against their captains.

1908 saw the end of the Black Patch War. Duke’s ATC trust was broken up in November under the Sherman Anti-Trust act. Prices were rising, as tobacco could now be sold at auction. The appeal of the PPA was diminished and their membership fell from seventy percent of the Black Patch to under fifty.

The Night Riders faded back into the community; the mask and the lash no longer ruled the night. Eight cent tobacco, and their own excesses, had put an end to their power and prestige.

The end game came a few years later, as an ambitious new prosecutor in Hopkinsville obtained an indictment for “conspiracy and destruction of property” against Amoss and other Night Rider leaders. Unthinkable just a year or two before!

The trial took place in Hopkinsville in 1911. Dr Amos and Dunning, his dear friend and second in command, were at the defendants’ table, while the courtroom was filled with hundreds, mostly supporters but with Night Rider victims among them, hungry for justice at last.

A small army of turncoats had been cultivated and prepared by the prosecution. Men who had once ridden with the Night Riders testified not only about the Hopkinsville Raid but about the secret oaths and procedures of the “Silent Brigade.” Yes, Dr. Amoss was the general, Dunning his lieutenant. The secret meeting places were exposed, the nocturnal oaths laid out in the light.

Dr. Amoss’s defense was direct and unadorned. The so-called “General” of the Night Riders was a simple country doctor. A parade of witnesses testified that he had been delivering a child or binding a wound at any time he was accused of directing Night Rider activities.

A Southern gentleman to the last, Amoss swore on the Bible to tell the truth; yet he had already sworn, on bended knees, to never betray the operations of the Silent Brigade. Which oath he would honor was never in doubt.

A Southern gentleman to the last, Amoss swore on the Bible to tell the truth; yet he had already sworn, on bended knees, to never betray the operations of the Silent Brigade. Which oath he would honor was never in doubt.

The trial was national news. Not only the Courier Journal but the Atlanta Constitution and The New York Times were on hand. The courtroom was silent as the jury filed in, after only forty minutes of deliberation, and delivered their verdict.

Not Guilty on all counts.

Nothing had changed, and yet everything had changed. It was over.

The disappointed and the triumphant left the courtroom together. Dr Amoss peacefully resumed his medical practice until he was diagnosed with a tumor and died in a sanitarium—in New York City, a few blocks from the palatial home of James B. Duke.

It was 1915, and the Black Patch War was already history. Hundreds of farmers, patients, sharecroppers and former Night Riders filed by his open casket to pay their last respects to the General as he was laid to rest in Caldwell County, in the heart of the Black Patch.

Hopkinsville, which once fell to Dr. Amoss’s Night Riders, today restages his trial annually, unabashedly if rather obliquely celebrating the Night Riders of the Black Patch War as the last “gallant” if somewhat troubling manifestation of the Old South.